by Rabbi Aryeh Klapper

Dear Friends,

Thank you so much for reading our Torah. Should you be so moved, here is the link to donate to CMTL. Your support is deeply appreciated and utterly necessary for our work to continue and our Torah to spread. G-d willing we’ll be in touch with more detail about that work early next year.

In gratitude,

Aryeh Klapper

Dear Rabbi Klapper,

Many years ago, I asked you whether the positronic robots in Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot were obligated to perform mitzvot. I think you answered with sources about golems and orangutans; all I remember is

being so happy that you took the question seriously.Now I have a hopefully more grown-up version of the same question: What are the responsibilities of programmers and users for the decisions and actions of artificial intelligences? Toward artificial intelligences? Do artificial intelligences have religious, ethical, or moral responsibilities?

I look forward very much to your reply.

With all best wishes,

Yoni Kohenson

Dear Yoni:

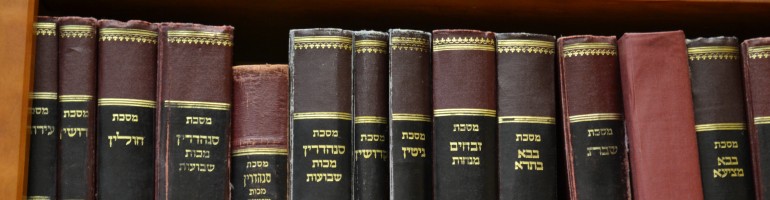

So great to hear from you! I remember the question well – I was 18 and you were 12, and it was the first time anyone had asked me a halakhic question with some sense that my answer would have authority. Happily my father z”l had taken me a few years earlier to a shiur on AI at an AOJS convention, and I remembered the speaker quoting Tif’eret Yisrael on the personhood of orangutans[1], and the amazing machloket acharonim about whether golems count to a minyan. (Q. Why did Rabbi Eliezer need to free his slave to make a minyan, when he could just have made a golem? Golems must not count! A. It would have been yuhara = arrogant/hubristic to make a golem for that purpose.) But those discussions assume that the question is whether other beings can be assimilated to the category of human.

Another useful starting point – I’m not sure I had read it then – is Rabbi Norman Lamm z”l’s “The Religious Implications of Extraterrestrial Life”. Rabbi Lamm works hard to show that Jews should not be frightened by the possibility that the universe contains other types of persons. What makes humans valuable is our quiddity/whatness and not our scarceness or uniqueness (although our value as individuals may be related to our ultimate uniqueness).

I’ve put a lot of weight already on the word “persons”. So let’s try to define it. I propose that it refers to the presence of three elements:

1. consciousness – by which I mean awareness of oneself as an integrated being. I’m consciously ignoring Sartre’s argument one cannot know that the cognizing and cognized selves are the same.

2. prudential judgment – by which I mean the ability to know which means are how likely to produce which consequences. I understand that human judgment is highly imperfect in this regard.

3. free will – by which I mean “hard” free will, the ability to make choices not determined in advance either by one’s environment or one’s own being. I am aware that some Jewish thinkers probably deny that human beings have this sort of free will, and that its existence cannot be philosophically demonstrated.

Requiring all three components of personhood for individuals creates grave moral difficulties with regard to infants (especially hypoencephalic infants), the insane, and so forth. The usual response is to require them for the species, and then extend the species’ umbrella to individuals. Extending personhood to nonbiological beings would problematize that – do computers have species? It might drive us to use the language of essences/souls instead.

Rabbi Lamm points out that halakhah is Terracentric. Earthlings finding themselves on a planet with permanent daylight everywhere, or habitable only at the poles, might adapt Talmudic models of time like “the person lost in the desert” and so forth. But it would make no sense for the Torah we have to be revealed on a planet without sunsets and pigs and other things that the Torah specifically regulates. G-d would give a different Torah to ETs who met our criteria for personhood. The same logic applies to persons who lack biological bodies, because “The Torah was not given to the ministering angels”.

This same issue applies applies to at least the prohibitions against incest and eating limbs from live animals among the Seven Noahide Commandments. So I don’t think that one can assimilate AI persons to the category of Noahides either, nor do I think ETs are Gentiles.

The best model I have for nonhuman persons is Rav Asher Weiss’s position on publicly held corporations. Rabbi Weiss holds (cf. the U.S. Supreme Court in Citizens United) that corporations are halakhic persons who are bound neither by Jewish halakhah nor Noahide law, and toward whom Jews owe no halakhic duties. Therefore publicly held corporations, even if Jews own most of their stock, can both charge and be charged interest to each other and to individual Jews. Rabbi Weiss nonetheless writes (Minchat Asher 1:105) that

“it seems correct that in all matters related to the prohibition of theft and robbery and the like, that are rational mitzvot between humans and their fellows – it is certainly obvious that these mitzvot are obligatory even on a corporation. It is forbidden to steal and it is forbidden to steal from it, and it is obvious that this body which has within it free-willed decisionmakers must behave in the manners of justice and integrity, because the world stands on truth and on law and on peace… but everything related to Torah prohibitions that are nothing but decrees of Scripture, such as chametz on Pesach, Shabbos, interest, and the like – there is fundamentally no prohibition of these with regard to the money of the corporation”.

I think the same is likely true of AI persons.

Rabbi Weiss gives no clear mechanism for constructing this reason-based system. I think AIs would have to play a significant role in recognizing and where necessary constructing any system under which they could be held accountable. For example, I am not at all certain that biological beings are likely on their own to properly determine how the concepts of life and death should be applied to AIs.

Corporations are not in any way conscious, nor do they have wills, free or otherwise, except via the aggregate wills of their human components. They are persons in a purely legal sense, not in the sense that AIs might become. I apply Rabbi Weiss’s model to them via kal vachomer, not because I think the analogy holds.

However, corporations might provide an apt model for considering human responsibility for creating nonperson machines that go of themselves and make morally significant decisions. My sense is that halakhah and Judaism do not yet have adequately developed frameworks for addressing individual responsibility for collective actions with no centralized decision procedure. We need this not just for AIs, but for climate change, labor-capital relations, and much more.

An immediate question specific to AIs is the extent to which we ought to be willing to devolve morally vital decisions to them. I’ll raise one specific kinds of issue here, and look forward to continuing the conversation. My question is whether there is any moral advantage to having humans make direct moral decisions even if an AI would make morally superior decisions. Suppose, for example, that a force of robocops would shoot fewer innocent people than the current force of human cops, with all other law enforcement outcomes remaining stable. Would there be any reason to allow or insist on maintaining a human force?

Here is one possible reason. Asimov accustomed us to think of AIs as rulebound and deductive on moral issues. But machine learning now functions very differently. AIs can be trained to make decisions by imitating human behavior as recorded in a cache of data, or else by studying the effects of their own past decisions, without necessarily following or developing any abstractly articulable rules. The result of outsourcing practical moral decision making to AIs may be the diminution of practical moral reasoning as a human experience.

In the context of campaign finance, I used the halakhic principle “it is more of a mitzvah to do the act oneself than to do it via agency” to argue that people should not devolve their political responsibilities and influence to corporations. A somewhat similar argument may apply here.

Another example: Imagine if there were (there may already be) an app that can decide the colors of stains for niddah purposes more accurately than the vast majority of current rabbis or even yoatzot; the app is trained, let us say, by shimush with Rav Yaakov Neuberger for many years. So on average women will get more accurate results using the app than by asking the rabbis available to them, with much greater convenience, and much less chance of embarrassment. Over time, we might lose all possibility of human psak because the app can’t explain its decisions other than in terms of a prediction of what Rav Neuberger would have decided. Should that be too great a loss, even though the results are better?

I hope these preliminary thoughts contribute positively to this developing conversation. Feedback and specific challenges and questions are of course welcome. I look forward to continuing learning from each other another year of learning together!

[1] Yakhin note 32 to Mishneh Kilayim 8:5; cf. Edgar Alan Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”. See now also the sources collected in Moshe Goldfeder, “Not All Dogs Go To Heaven: Judaism and Beastly Morality”.